Why designers love Oscar Wilde

I doubt that most fashion designers are enthused readers of Oscar Wilde’s epigrams, yet the influence of his wardrobe on menswear this autumn/winter season is marked.

The predominant trouser silhouette — one whose hem slices someplace between kneecap and upper thigh, present at Dior, Prada, Louis Vuitton and anywhere else you name — could have taken a cue from Wilde’s velvet knee-breeches. Shirts were cut loose and bloused, sometimes with their necks knotted with giant bows, while floral corsages bloomed on shoulders and throats at Dolce & Gabbana and Valentino. There’s a general mood of dandyism and flamboyance, of sartorial statements as bold as Wilde’s prose.

For some designers, the connection goes deeper than a seasonal look — Wildean propositions are at the root of the style of CFDA Menswear Designer of the Year Willy Chavarria and the clothes of Steven Stokey-Daley, the young LVMH Prize-winning London men’s designer. Across several seasons, Chavarria has shown hyper-luxurious, dandyish menswear in lustrous silk and satins, blazers pinned with overblown roses, cloaks flowing. Meanwhile, the three-year-old SS Daley label is directly inspired by the homosocial bonding of British public schools, with flamboyant wide-legged tailoring and the kind of wide-collared romantic shirts favoured in the past by Wilde and today by Harry Styles, an SS Daley fan.

Wilde’s style wasn’t by chance. It was a carefully curated presentation, invented during his studies at Oxford (he also lost his native Irish accent there). He once observed he “had been sometimes accused of setting too high an importance on dress”, and his interest in his own attire is easily evinced by the stream of photographs of him.

In particular, examine the promotional images taken on his first lecture tour of the US in 1882, where he is dressed in his hallmark outfit of knickerbockers, knotted cravats and swaggering draped capes, wide-brimmed hat rakishly angled, curling hair falling to his shoulders. Wilde was advertised as much as an aesthete as a poet on that debut tour — and what he wore seemed to interest people just as much as what he read. In February of that year, he wrote to his American tour manager Colonel WF Morse that audiences “were dreadfully disappointed in Cincinnati at my not wearing knee-breeches”. He didn’t make the mistake again — indeed, he continued to dress notably and eccentrically for the rest of his life.

Though Wilde’s looks were well documented, and he evidently took great pains over his appearance, he was no fashion plate. “He is not heavily built but looks like a not particularly active athletic young man,” wrote the New York Times, somewhat ungraciously, when the then 28-year-old Wilde landed in the city in January 1882, “with a rather massive chin and a nose of more than ordinary size”. In later years, Wilde’s dental hygiene was so bad that he consciously hid his discoloured teeth with a hand when laughing.

Wilde’s breed of “artistic” dressing became synonymous with homosexuality after his 1895 trial. It is even hinted at before: “Affected effeminacy” is a phrase used by the New York Times in 1881, the same year Wilde’s personal style was caricatured in the Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera Patience. In an 1891 letter to the Daily Telegraph, Wilde wrote “If one is to behave badly, it is better to be bad in a becoming dress” — tellingly, he had begun his first gay relationship in 1886.

Yet by the 1890s Wilde’s wild style had calmed down somewhat: portraits in that decade see him dressed in perfectly tailored frock coats and double-breasted tailoring, the archetypal Victorian gentleman. His hair was cut respectably short. But there was always a frisson of subversion in his style: in 1892, he first sported his soon-to-be signature green carnation, and had one of the actors on the opening night of Lady Windermere’s Fan wear one too. Sported by Wilde’s predominantly gay male circle, the flower rapidly became a coded emblem of homosexuality.

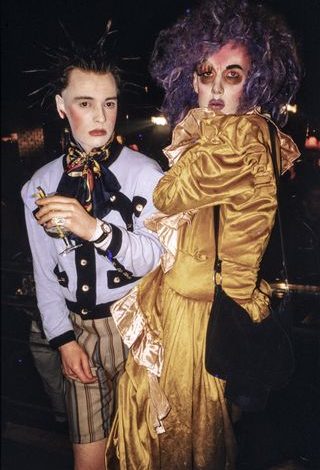

The Wilde look has been periodically revived as an outward expression of artistic and sexual freedom. In the liberated 1960s, alongside revivals of Art Nouveau and a vogue for the graphics of Aubrey Beardsley (who illustrated Wilde’s Salome) following a 1966 V&A retrospective, peacocking young men of various sexual persuasions dressed in velvet blazers and poetic blouses, and grew their hair long à la Oscar. The then young and radical couturier Yves Saint Laurent proposed beribboned haute couture knickerbocker suits for women in 1967 that were dead ringers for Wilde’s: some conservative establishments refused entry to women wearing them. In the 1980s, similar styles were sported by the hedonistic, gender-bending club kids of the New Romantic movement.

That fits, given that what Wilde wore actually was the anti-fashion, almost punk look of his day. Wilde’s clothes were termed Aesthetic Dress, aligned to the art movement celebrating art for art’s sake. His wife Constance was one of the founders of an affiliated group, the Rational Dress Society, which proposed jettisoning cumbersome Victorian clothes in favour of simple styles cut to the lines of the natural body. They pushed against contemporary fashion trends — which Wilde memorably declared “merely a form of ugliness so absolutely unbearable that we have to alter it every six months”.

That famous line, incidentally, first appeared in an otherwise obscure Wilde essay titled “The Philosophy of Dress”, written for the New York Tribune in 1885 and lost until 2012, when it was recovered in book form by Wilde historian John Cooper. Within, Wilde rails against the creations of the fashion house of Charles Frederick Worth — the Dior of its day, which invented the notion of the designer label and fashion seasons — and against fashionable tropes such as aniline dyes, fussy frills and ostentatious millinery.

Re-reading the tract today, Wilde’s points seem markedly modern. For Wilde, “the beauty of dress, as the beauty of life, comes always from freedom” — and this was written a good century and a half before athleisure. In an 1884 piece for the Pall Mall Gazette, Wilde even asserted that “there is absolutely no such thing as a definitely feminine garment”. It’s a revolutionary idea in the paralysingly gendered landscape of 19th-century fashion, and one still opposed by some quarters today.

Those ideas, more than the cut of particular garments, may explain the enduring appeal of the Wilde look. He was a free-thinker, his clothes followed. We could all learn a lesson.

Follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen